|

Kotlas - Waterville Area Sister City Connection P.O. Box 1747 Waterville, ME 04903-1747 Write to Us |

|

|

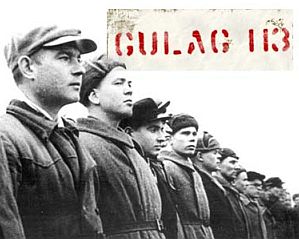

Home > News > 2006 > Gulag 113 Gulag 113: A Tale of Survival

By Gregor Smith The Kotlas Connection's Russian Day brought the New England premiere of a new documentary about Kotlas and the Gulag, the system of prisons, labor camps, and remote settlements that flourished under Stalin during the 1930's and '40's. In Gulag 113, Toronto filmmaker Marcus Kolga and his 89-year-old grandfather, Eduard Kolga, retrace the latter's journey from his native Estonia to a logging camp near Kotlas and back again. The 46-minute film also includes archival footage and an interview with Washington Post columnist Anne Applebaum, whose latest book, Gulag: A History, won the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction in 2004. The story begins in 1939, when Soviet forces invaded and annexed Estonia, a Baltic Sea republic that had broken away from the Russian Empire during the Bolshevik Revolution. Following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union two years later, the Soviet army drafted all Estonian men under the age of 50. At first, Eduard Kolga, then 25, wanted to hide in the forest, but Soviet authorities had threatened to torture and execute any evaders and their families. To spare his family that gruesome fate, he surrendered. Kolga and the other 50,000 Estonian men were not sent to fight, however, but were loaded onto cattle cars to be taken to Gulag labor camps deep within Russia. After several stops, Kolga ended up at Camp 113, a logging camp in deep woods near Kotlas. There the underfed and under-clothed inmates lived in crude huts. Starvation, disease, hard labor, and extreme cold took their toll. During the horrific winter of 1941-1942, when the temperatures frequently dropped below The following spring, the Soviet army, decimated by casualties, transferred the surviving inmates to a Red Army training base and then to the front. Amidst the chaos of battle, Kolga was able to escape behind German lines in late December 1942. After a stay in a German field hospital, he returned to his family farm in the Spring of 1943. He, his wife, and twin sons born during his absence later fled first to Sweden and then to Canada. The younger Kolga's motivation in making the film was twofold: to preserve his family's history and to raise awareness of the Gulag system and its victims. "My grandfather's story was, for one reason or another, obscured throughout my childhood and only came to light when I began asking about it while I was in University," he writes. "I encouraged him to chronicle his experience, if for nothing else, as a record for his own family." Ever since, the younger Kolga had wanted to make a documentary about his grandfather's travails, but it wasn't until he obtained a grant from Rogers Media, a Canadian television broadcaster, that he was able to act on his desire. The elder Kolga was initially reluctant to make the film. To relive his saga would be a trial, both physically and mentally. He also feared that if he returned to the former Soviet Union, he could be arrested for having deserted the Soviet army six decades earlier! When his grandson explained the historical importance of the endeavor, however, Eduard Kolga readily put aside his reservations. The younger Kolga continues:

In July 2004, the two Kolgas and a film crew spent two weeks in Russia and Estonia shooting the documentary. They shot 31 hours of footage and, apart from an unfriendly guard outside a prison where Eduard Kolga had once been incarcerated, most of the people they encountered were enthusiastic about the project.

The Kotlas Connection had a small role in the making of the film. When the younger Kolga was doing research that spring, he found a description of Kotlas Gulag facilities on the Kotlas Connection's web site. He then wrote to the site's creator, Gregor Smith, who put him in touch with Irina Dubrovina, a founder of Sovest' ("Conscience"), a Kotlas organization dedicated to teaching Russians about the Gulag and seeking compensation for its victims. Dubrovina and several other local activists appear in the film. Gulag 113 is Kolga's first documentary. Since its debut on Canadian television in November 2005, Gulag 113 has been shown at film festivals in Chicago and Washington. It aired on Swedish television in May 2006 and was shown in theaters in Estonia in May and June. The Toronto filmmaker is now finishing his second film, a documentary about the January 1945 sinking of a German refugee ship, the Wilhelm Gustloff, by a Soviet submarine. According to Kolga, that sinking "ranks as the worst maritime disaster with nearly 10,000 dead. The story is told from the perspective of survivors / witnesses and ultimately seeks to examine the politics of memory as it pertains to Germans and the Nazi legacy." Kolga is also the founder of graphic design firm, a freelance writer who devotes an "unhealthy amount of time" to Canadian politics, and father to two young sons. His hale grandfather is enjoying life in an Estonian retirement home in Toronto. For more information about the film, visit its web site: www.realworldpictures.ca Update: On October 31, 2007, Eduard Kolga died of respiratory complications shortly after being admitted to a Toronto area hospital. He was 93 years old. |