|

Kotlas - Waterville Area Sister City Connection P.O. Box 1747 Waterville, ME 04903-1747 Write to Us |

|

|

Home > About Kotlas > History A History of KotlasIn 1997, to commemorate the eightieth anniversary of the incorporation of Kotlas as a city, the Kotlas Local History Museum published a booklet containing a history of Kotlas and photographs of the city, past and present. The following is a slightly abridged translation of the text. A. Denisova, N. Melnikova, and N. Nikolayevna, staff members at the Kotlas Local History Museum, wrote this history; and Pat Hanson translated it. Greg Smith edited the translation and added the italicized annotations, section headings, and picture captions. The photographs are from the museum's archives and appeared in the original booklet. The Coming of the RailroadThe growth of the internal market and of the international relations of Russia at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries helped to draw Northern Russia into the economic life of the country. Since ancient times a large quantity of lumber, fish, furs, pelts, felt goods, and other products had gone from here into the heart of the country. Grain, iron, fishing tackle, gunpowder, and machines had come here from the central regions and from Siberia, and a good part of these goods went abroad. At the end of the last century, the creation of large industry, especially timber processing, was picking up speed in Northern Russia. The large state- owned forests, relatively cheap labor, convenient river and sea routes, and the demand for timber in the European markets led to the development of the timber industry. Kotlas, situated at the active intersection of the waterways of European Northern Russia, had for many centuries not taken advantage of its fortunate, natural location, remaining a small village. The population was sparse, and the soil was poor — partly loam and clay and partly sand. The climate was severe, with sharp changes in temperature and prolonged winters. Mainly, the inhabitants worked the land, using only primitive tools — the old wooden plow, the harrow, and the curved scythe. Their basic crops were rye and barley. The low productivity didn't even cover their most basic needs. To make ends meet, many peasants took seasonal work; they were called "drifters". The drifters of Kotlas area villages were mainly builders, stone workers, carpenters, and stokers.

Traveling through Northern Russia, the Russian writer A.A. Kolychev, spent some time in Kotlas in 1894. This is how he caught sight of Kotlas:

In the summer of that same year, the Russian government organized an expedition to Northern Russia under the direction of the Minister of Finance, S. Yu. Witte. [Sergei Yulyevich Witte (1849-1915), pronounced "vit-te" is best known today as the lead Russian negotiator in the talks that ended the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. The talks were held at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, on an island in the river that separates Maine from New Hampshire.] Included in the expedition was a commission that would determine where the railroad route to Northern Russia would be built. One of the members of this expedition was the Russian writer and publicist, Ye. V. Kochetov. He wrote:

Thus Archangel would become an export center. The line would also give an outlet for grain from Vyatka [called Kirov during the Communist era], and could in the future, connect the coal mining region of Perm with St.Petersburg, the center of manufacturing. In 1895, "by the highest command," the order was given to the Transportation Ministry to build the railroad line Perm-Vyatka-Kotlas. The route from Perm to Kotlas was broken down into 9 sections, and the length of the line was 812 versts. [A verst is an old Russian unit of distance that is no longer used. 1 verst = 3500 ft.; thus, 812 versts = 538 mi.] The construction was financed by merchants and industrialists interested in exporting Siberian grain, butter, flax, and furs to foreign markets. In January of 1899, the line Vyatka-Kotlas opened for temporary use, and in October, the Commission of the Transportation Ministry that was created to bring the railroad into service concluded that The industrialists who had financed the railroad were counting on a very great flow of freight, so that they could quickly recover their costs, but their hopes were not well-founded. In 1900 the newspaper Nash krai ["Our Country"] announced that in a twenty-four hour period the station at Kotlas receives "only a couple of trains, one of which is a combination freight and passenger train, but it is rare that there are as many as one to one and a half cars of third class passengers."

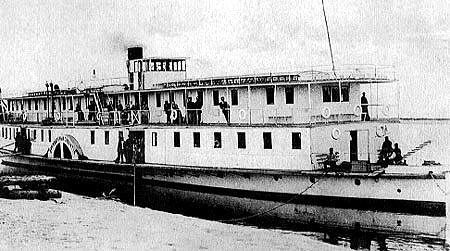

The second half of the nineteenth century marked the beginning of navigation of the Northern Dvina by steamship. The initiators of the steamship business were an Archangel merchant and a commercial consultant who, together with other merchants, formed the Northern Dvina Steamship Corporation, with headquarters in Veliky Ustyug [a city 40 miles south, up the Northern Dvina from Kotlas.] In August of 1858, the organizers of this corporation completed the first exploratory navigation up the Northern Dvina. Although shallows prevented the ship from reaching its intended destination, the voyage opened the era of steam navigation. At first there were only two steamships and 18 barges in the fleet. The volume of freight didn't exceed 500,000 tons, and there were few passengers. As the volume of freight expanded, the number of vessels grew; the passenger count increased; and the profits of the ship owners grew. River transport developed particularly fast after the railroad line from Perm to Kotlas was opened. In 1898, a new partnership of ship owners, Northern Shipping Kotlas-Archangel-Murmansk sprang up, with its headquarters in Archangel. The main task of the new partnership was to ship Siberian grain that had come by rail to Kotlas from Kotlas to Archangel on the Northern Dvina. The first steamship with grain left Archangel for Europe in 1899. The first two-decked ships started navigating the Northern Dvina in 1902. These were the comfortable passenger ships that could at the same time transport various kinds of freight containers — crates, bales, barrels, etc. — in their very spacious holds. In 1901, there was already a system of lighted buoys for a stretch of 562 versts [373 mi.] along the Northern Dvina. In 1910, a floating system of spar-buoys and buoys with partial illumination was set up at the shoals of the Vychegda [a tributary that flows into the Northern Dvina at Kotlas.]

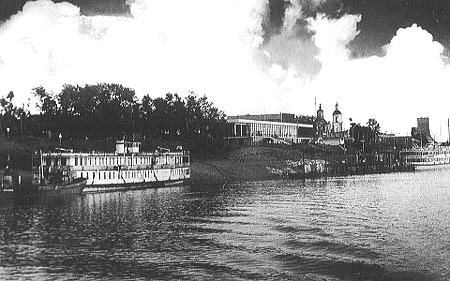

In 1901, the writer Kolychev again visited Kotlas, and now he saw a completely different picture. "In 5 to 8 years Kotlas has changed greatly, especially in its external appearance. The peasant homes have been moved farther toward the forest; the banks have been reinforced; and below, right beside the river, rails have been laid right up to the wharf. Approximately a half a verst from the church are attractive grain elevators made of boards and decorated with blue paint. The churches, as formerly, can be seen from a distance, but are no longer in the midst of blackened peasants' huts. Now in front of the church stretches an enormous square with the clean yellow buildings of the railroad." After the railroad had been brought to Kotlas, yet another famous Russian writer, N.A. Leykin, spent some time here. He wrote in his memoirs: "Kotlas is a small village In 1910, a commission from the Vologda provincial zemstvo [a local elected assembly] came to Kotlas. It concluded that "with the coming of the railroad, Kotlas has begun to develop noticeably and increase in population. It won't be long before the two neighboring villages of Petrukhinskaya and Zhernakovo will join with Kotlas and change it into a small city, the economic significance of which will not be subject to the slightest doubt"

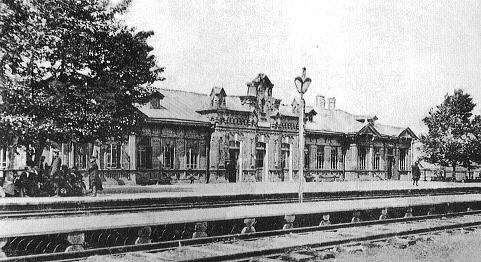

After the building of the railroad, the outward appearance of Kotlas changed and its life became noticeably more active. Now it was a small community consisting of a railroad settlement and several villages and churchyards. Among the most noteworthy buildings was the railroad station, on both sides of which were located five one-story wooden buildings where the office workers of the station lived. Near the station were the stone buildings of the railroad workshops and depot. There was no community self-governing body, but there were three administrators: civil, port, and railroad. Order was maintained by a police officer, a village constable, and the railroad gendarmerie. The amenities consisted of raised wooden sidewalks along the streets in front of the houses. The shore of the Northern Dvina, the favorite place for recreation of Kotlassians, was pretty nicely improved for those times. For disembarking from the wharf to the shore, there was a nice wide stairway with a pretty terrace and two towers. From the terrace opened up magnificent views of the beautiful Northern Dvina and the wooded shores in the distance. Along the stone-lined road from the wharf to the railroad station were many stalls where, in periods of navigation, a lively trade in foods, manufactured goods, and handicrafts was carried on.

There was no health care system as such in Kotlas, but in June of 1910, in connection with the formation of a railroad station, a nursing station was set up in Kotlas. Patients who needed hospitalization were sent to the hospitals in the cities of Solvychegodsk [a town 15 miles to the northwest, up the Vychegda from Kotlas] and Velikiy Ustyug.

The only school in Kotlas was a three-year parochial school. It was housed in an old building with low ceilings and a single classroom, where all three classes studied together. A new two-story school building was constructed near the church in 1903, and in 1907, at the initiative of railroad administrator A.M. Sokolov, a two-class railroad technical school opened. Upon finishing this school the graduates went to work for the railway as telegraph operators, station masters, and assistant station masters. Others worked at the depot as metal workers, lathe operators, assistant engineers and engineers. The first graduation took place in 1909; there were 13 boys and 3 girls. The People's House, which was the cultural center in Kotlas at that time, was also built thanks to A.M. Sokolov. In the People's House, there was a tearoom, a stage and an auditorium. There was an amateur theater troop in Kotlas, which put on plays in the People's House. Until the building of the railroad there were no manufacturing enterprises in Kotlas, except a primitive, 18th-century sawmill 4 kilometers from Kotlas. In the beginning of the 20th century, three steam-operated gristmills appeared, and at that same time four bakeries, employing 20-40 people, were opened. They produced crackers and kalaches [a white wheat-meal loaf] and sent them off to Archangel. There was a highly developed retail and wholesale trade in various goods, especially flour. Merchant stall, stores and taverns opened. The stores were located mainly in the village of Zhernakovo, where there were two-story wooden merchants' houses with stores in the lower floors. With its transformation into a trade center, Kotlas became of interest not only to Russian industrialists, but also to foreigners. The Siberian merchants who had subsidized the building of the railroad founded a number of commercial firms in Kotlas, and branches of various banks started cropping up. Soon the trans-shipping of grain fell into the hands of foreigners, and then the English and Americans took the leading role in Northern Russian river navigation. Warehouses were built at the river shore for storing the freight which was coming to Kotlas. As was noted in the report of the zemstvo commission, the warehouses "could hold up to 8,000,000 poods [about 64,000 tons] of various stored goods. [A pood is a former Russian unit of weight, equal to about 16 lb.] It will soon

The transformation of Kotlas into a transport center and the development of industry, trade and culture called for turning it into a city. In 1917 the district police chief reported:

That is how Kotlas was in 1917. On the May 3, 1917, a meeting of the Council of Ministers of the Provisional Government considered the question of transforming Kotlas into a city, and on June 3, the Provisional Government made the final decision to give to Kotlas the status of a city. [In the Gregorian (Western) calendar, these dates would be May 16 and June 16, respectively. Russia did not adopt the Gregorian calendar until 1918.]

1917 brought other changes to Kotlas. In April, a Soviet ["council"] of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies was formed, [as they were in cities and towns throughout Russia following the February Revolution.] It included representatives of the peasants of the surrounding villages. An arbitration body for settling labor disputes between workers and employers, as well as an extraordinary commission for fighting against counterrevolution and a revolutionary tribunal functioned under the auspices of the Soviet. From the very first days of service the Soviet became an organ of the new revolutionary forces. Elections to the City Duma took place in the summer of 1917, but after the victory of the October Revolution all power passed to the Kotlas Soviet of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies. In the winter of 1918, the water transport workers of the North began to nationalize the fleet, the shipyards, the warehouses, and other property belonging to the ship owners, just as soon as the decree of the Soviet of People's Commissars "On the Nationalization of the Merchant Fleet" reached them. In all 67 passenger boats, 301 tugs, 707 barges and landing platforms, and 433 auxiliary and other vessels in the Northern Dvina basin were nationalized. With the opening of the navigation season in 1918, an active transfer of military equipment from Archangel via the Northern Dvina to Kotlas began, as the threat of the seizure of Archangel had grown due to the landing of the first forces of the interventionists in the region of Murmansk [in March 1918]. [After the Bolsheviks came to power in November 1917, they immediately sought to extricate Russia from World War I. In December, they arranged an armistice with the Central Powers and followed it with a peace treaty, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in March1918. The Allies opposed the treaty, because it allowed the Germans to transfer troops from the Eastern Front to the West. The Allies decided to send troops into Northern Russia to re-open the Eastern Front, protect munitions depots at Archangel and Murmansk, and provide support for the various Russian, anti-Bolshevik, "White" armies trying to overthrow the revolutionary government. Fifteen hundred British troops landed at Archangel on August 2, and 5000 Americans arrived five weeks later. The Allies thought that their forces would be able to move south up the Northern Dvina to the railhead at Kotlas and then to Vyatka to join a larger and better armed Czechoslovak force that would fight its way west along the Trans-Siberian Railroad. In mid-September, the Allies took Shenkursk, which was then the second largest town in the Archangel Region and is strategically located on the Vaga River, a western tributary of the Northern Dvina that joins the larger river 140 miles northwest of Kotlas. The Allies were unable to hold any towns beyond Shenkursk for long, however, and had to quit Shenkursk in late January 1919 after a massive Boshevik advance.]

An evacuation commission was set up in Kotlas to receive the shipments, rerouting them to the center of the country and organizing an artillery depot. With the occupation of Archangel and the advance of the Anglo-American troops and the counterrevolutionary forces up the Dvina toward Kotlas, the threat of capture of the depot was imminent. It was decided to evacuate the supplies of the depot farther inland. As soon as the news of the events in Archangel became known, Kotlassians prepared to defend the city. Troops were mobilized to be sent to the front, and Red Army brigades were organized. Measures were also taken to protect the military supplies. A state of siege was declared in Kotlas in August 1918. In September, several lines of mines were laid and the channel of the Dvina was blocked 120 kilometers [75 miles] down river from Kotlas in order to impede the advance of the enemy toward Kotlas. An exceptionally dangerous situation developed on the Northern Dvina (Kotlas) front in the fall of 1918. The interventionists concentrated up to two thirds of their forces here. Their immediate goal was to capture Kotlas and thus gain access to Vyatka [Kirov]. They were hurrying to finish the operation before the season of navigation ended on the Dvina [i.e., before the river froze, in November]. After the interventionists had advanced 300 kilometers [190 mi.] by water they were stopped by parts of the Sixth Army and the Red Northern Dvina flotilla.

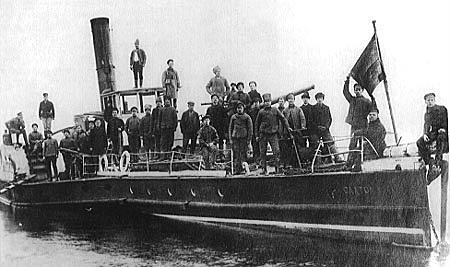

The Northern Dvina river flotilla had just been formed. Retreating from Archangel under pressure from the superior forces of the enemy, the river boatmen took 60 riverboats and barges up the Dvina. In addition to these vessels, about 90 vessels of various types were collected along the Northern Dvina from Archangel to Kotlas. On this basis the Red Northern Dvina river flotilla was formed. Only some of the boats were armed. P.F. Vinogradov was the organizer of the flotilla. [According to the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd ed., the fleet initially included "three armed steamships, a patrol tugboat, and a land company of 142 seamen, [but] by September 1919, it had been augmented by nine gunboats, five floating batteries, 11 minesweepers, five patrol vessels, eight patrol cutters, 35 vessels of various other classes, a landing and reconnaissance detachment, a detachment of seaplanes." Although Pavlin Fedorovich Vinogradov (1890-1918) founded the fleet, in August 1918, the St. Petersburg native did not command it for long; he died in battle only a few weeks later. The fleet itself was disbanded in May 1920, its work done.]

Correctly evaluating the significance of Kotlas in the struggle with the enemies of revolution, Vinogradov spared no effort to strengthen the defenses of the region. He understood that if his forces could hold back the movement of the enemy along the Northern Dvina until frost set in, the interventionists and counter-revolutionaries would be dealt a serious blow. Quickly gathering his forces, Vinogradov undertook battle at Dvinskiy Bereznik on the night of August 10-11, 1918. [The Allies had established a supply base in the town, which lies 150 mi. down river from Kotlas, just above the confluence with the Vaga.] Approaching Bereznik with the lights extinguished on the vessels of the flotilla, Vinogradov began a decisive defeat of his opponent, opening, in his words, a "stormy massive barrage". The battle lasted two hours and ten minutes. The enemy's losses were great. In this small encounter, the enemy was for the first time turned back on the Northern Dvina, and for the first time in the history of our steam-powered fleet, passenger boats and tugs were successfully used in a river battle. The order of V.I. Lenin "to organize the defense of Kotlas at all costs" was decisive inthe reinforcement of the defenses of Kotlas and in the formation of new military units and the Northern Dvina river flotilla. It's difficult to overestimate the strategic importance of Kotlas in the anxious days of August 1918. New reinforcements kept arriving in the city. A Kotlas fortified district was created. In November, the 18th Artillery Division, which was named for Kotlas, was organized. This division, along with the flotilla, firmly held the defense. The most significant outcome of the military operations of 1918-1919 was that the plan of the interventionists to connect with the troops of Kolchak [i.e. the aforementioned Czechoslovak force] was foiled. [Admiral Alexander Kolchak commanded the Russian opposition forces in Siberia, and, from November 1918 to January 1920, headed the opposition government, based first in Omsk and then in Irkutsk.] Kotlas became a strong attack base for the Red Army against the interventionists and the White Guard [i.e., the anti-Bolshevik Russian forces, collectively], the main base of the Northern Dvina armed river flotilla. Through it passed all the necessary supplies for the Northern fleet: equipment, military supplies, food, materials and fodder. Military units were sent off from here to the front. [With the armistice between the Allies and the Central Powers in November 1918, the main justification for the intervention evaporated, but the orders to withdraw Allied troops from Russia did not come until the next spring. The Americans pulled out of Archangel in June 1919; the British stayed until early October. By the middle of the following February, White resistance had collapsed throughout the rest of Russia; Kolchak had been executed by the Bolsheviks; and the Red Army was advancing on Archangel. On February 19, an icebreaker carrying Archangel's military, political, and business elites and their families chopped its way out of Archangel's frozen harbor, bound for Norway. The next day,the Red Army arrived, ending the Northern Russian struggle against the Bolsheviks. Among the passengers on that icebreaker are believed to have been Alexei von Rankhner, a student and "volunteer lieutenant", and Lydia Yestifeyeva, a recently-divorced nurse. They met for the first time on the ship — he having run across the ice after the ship as it was chugging out of the harbor. They subsequently married, settled in Yugoslavia, and raised twin daughters, one of whom eventually co-founded the sister city effort in Waterville, Me. Her name is Natalia Alexeyevna von Rankhner Kempers. While we can't be sure that Natalia Kempers's parents were on the particular ship that departed on February 19, we do know that they left Archangel by icebreaker during the winter of 1920, not long before the city fell.]

After the battles of the Civil War died down, the inhabitants of Kotlas turned to building the city and resurrecting the railroad and river transport systems, which had been destroyed or fallen into decay. A development plan was needed to properly carry out the management and construction of the city. In 1922 the first city planning project was put together with a population calculated at 20,000. Development proceeded according to this plan with primarily one-story wooden family homes. Nobody bothered with amenities. The [unpaved] streets were impassable in the spring and fall. There were no street lights, and the inhabitants lit their houses with kerosene lanterns. In the 1920's and 1930's when the construction of industrial enterprises in the country began, it was necessary to purchase some of the equipment for them abroad, in exchange for lumber and saw-timber coming from the North. Lumber was needed for new construction, mine shafts, and agriculture. Logging in the northern regions expanded quickly. Kotlas, located on the main timber-float routes, grew together with the logging. A large-scale trans-shipping base was set up in Limenda [a district of Kotlas] in 1924. Spur railway tracks were laid to this base. This timber base handled the loading of timber from the Vychegda into railway cars. Soon it became necessary to create a second timber base in Kotlas. In 1931, in the southwest outskirts of Kotlas, the Boltinskaya timber trans-shipping base was founded. Its task was to roll out and load logs felled in the basins of the Yug and Sukhona Rivers [which converge 35 mi. south of Kotlas to form the Northern Dvina]. Some of this timber went to the internal markets, but a significant part was made into railway sleepers and pit-props. Sawmill No. 46 was opened in Kotlas in 1934. A lot of lumber was transported by water. As the fleet of the Northern Dvina wore out and ceased to be able to handle the cargo, construction began in Limenda of a boat-building and repair yard. The first building of the new facility, the mechanical shop, was set up in 1930. Construction of the boiler house, foundry, and woodworking shop began the same year. The economic presence of Kotlas took form during the years of the first five-year plans. With the filling out of the fleet Northern river steamship line, the turnover of freight at the Kotlas river station began to grow quickly. Almost half of the freight consisted of grain. The Kotlas station expanded; a new freight yard was created; and the port was equipped with loading and unloading mechanisms. Much freight was dispatched by rail. The Kotlas railroad workers each year increased the average daily runs of locomotives and successfully struggled to economize in fuel, resources and materials. Construction of the workshops for the repair of railway wagons began in 1936.

In the prewar years Kotlas took shape as a significant center for transportation and industry. According to the census there were already around 27,000 inhabitants in Kotlas in 1939, including 6,000-7,000 industrial workers.

At the end of the 1920's and beginning of the 1930's, the main housing units were located between the railway line and the river shore. Later the land south of the railway was developed. It was cleared of forest and brush; new arterial roads and streets were laid out; and blocks of houses sprang up. Construction was purely of wood. In 1930 a radio broadcast tower with a power of 5 watts was built. The same year the local newspaper Za sotsialistichesky Sever ["For a Socialist North"] began publishing. Construction of the city electric power station commenced in 1937, and at this point many of the homes and all of the schools, institutions, and cultural centers received electrical lighting. The network of cultural institutions expanded; the railroad workers' club was built; and in 1927 the Kotlas District Library opened with books gathered from the citizens. In 1940, there were already 7 libraries open in Kotlas with more than 100,000 books. The children's branch of the library was formed in September of 1941. In December of 1935, the Northern District Executive Committee decided that a theater should be organized in Kotlas. In January of 1936, the inhabitants of Kotlas saw their first performance. At the end of the 1930's, there were three secondary schools and one school with fewer grades. In addition there were schools in Limenda and Boltinka and also two schools for adults. Among the institutions serving children in Kotlas there were nine kindergartens, five nurseries, a camp for 186 children, and a Pioneer club [i.e. a Communist boy and girl scout organization]. Among the health care facilities in Kotlas were four hospitals: a city hospital, one at the sawmill, one at the factory in Limenda, and one for the river transport workers. In the city, there was a polyclinic, an ambulance, a birthing center, two health centers, two midwife stations, a first aid station for the river workers, a medical-midwife station for the railroad, and a school for nurses. The 1930's were not only years of successes and accomplishments. The wave of political repressions touched Kotlas too. Kotlas became a center for exile and prison camps. Here were sent dispossessed kulaks [peasant farmers who were financially better off than their neighbors] and those convicted under Article 58, the so-called "enemies of the people". In 1938 the [regional] headquarters for the Gulag was built. It was given the task of bringing in the materials necessary to construct the railroad from Kotlas to Vorkuta and the railroad bridge over the Northern Dvina. [For more information, see "Kotlas and the Gulag".] And so the prewar years were an important period in the history of the development of Kotlas. Important enterprises were built in the city, giving it the right to call itself an industrial center. Kotlas began to play a significant role in the economy of the country.

The treacherous invasion by fascist Germany halted the peaceful labor of the inhabitants of the city. In the first days of the Great Patriotic War, large meetings took place at the enterprises in Kotlas. The citizens of Kotlas, like all the Soviet people, expressed their readiness to stand in defense of the Fatherland. Civil defense units were set up in the enterprises and institutions. General obligatory military preparedness of the population for anti-aircraft defense began. All the enterprises and institutions dug bomb shelters and enforced a blackout in the evenings. First-aid patrols were formed. Fifteen hundred people, more than half of them women, were sent from the city and the district to Karelia to build fortifications. [Karelia is a Russian autonomous republic adjoining Finland.] These people from Kotlas built bridges, crossings, and roads, subjecting themselves to strafing by German planes. Eight of them perished, including the commander of the construction battalion. Citizens of Kotlas also mobilized for fortification work near Vologda, [a city 330 mi. north of Moscow]. As soon as the mobilization was announced, people went to the mobilization points asking to be sent to the front. Only 24 hours after the beginning of the war, the first group mobilized by the military command post was sent to the front. It was made up of workers from the Limenda shipyard. In early July 1941, a center for evacuees from districts temporarily occupied by the enemy was set up in Kotlas. The evacuation center was in the building of the railroad workers' club. All of the evacuees received housing and were put to work in the city's enterprises. A great effort was made to set up Evacuation Hospital No. 2520 in Kotlas, with 400 beds for treating wounded and sick soldiers. The hospital occupied several buildings, including the surgical wing of the city hospital and a school. The first wounded from the Karelia front were admitted to the hospital on August 15, 1941. Hospital personnel worked around the clock and the population helped in any way they could. "Everything for the front, everything for victory!" That was the motto under which the whole country toiled during the difficult wartime period. The enterprises of Kotlas quickly converted to military production for the Red Army. Thus the Limenda shipbuilding and repair factory had to master the production of field bridges and housings for 100 kilogram bombs. It took only a month and a half for the engineers and workers of Limenda to convert from civilian to military production. At the factory the places at the bench left by the men who had gone to the front were filled by women and teenagers.

During the war years, after the completion of the North-Pechora railroad, Kotlas became an important transportation junction. [The Pechora is a river in northern Komi, the Montana-sized autonomous republic between the Archangel Region and the Urals.] The first train was sent from Vorkuta on the new line on December 28, 1941. In the middle of the summer of 1942 the North-Pechora line was put into regular use from Vorkuta through Kotlas to Konosha. In this way the natural wealth of the polar region began to work for the defense of the country. The self-sacrificing labor of the railway workers and builders helped to assure uninterrupted supplies of coal and lumber for the industrial enterprises in the center of the country and the Urals during the war. [Prisoners in the Gulag also helped build this railroad. See "Kotlas and the Gulag".] Kotlas railway workers assured the uninterrupted and accurate passage of freight. The Kotlas river port also had an important role in the war years. From the beginning of exploitation of the North-Pechora railroad, the volume of loading and unloading work increased sharply. Thousands of tons of coal and liquid fuel from the Pechora region passed through the river port destined for the Northern Fleet. Voluntary workdays on Saturdays and Sundays were regularly organized in the city and the earnings from them went to a fund for the defense of the country. Money was collected for tank columns and airplane squadrons, and personal savings and war bonds were contributed to the fund for national defense. The inhabitants of Kotlas worked selflessly at home and fought bravely on the front. At the very beginning of the war, in 1941-1942, a division was formed in Kotlas which later brought everlasting glory upon itself. In October of 1943, the division participated in the breach of the enemy's defenses and the liberation of the city of Nevel [300 mi. east of Moscow, on the s border with Belarus.]. For its successful military action in this operation the division was given the honorable name 28th Nevelskoy Red Banner Artillery Division. Kotlas members of the Nevelskoy passed the roads of the war from Kotlas to Bucharest together with the Division. Many Kotlassians fought in the 263rd Sivashskoy Division, which defended and liberated Sevastopol. Our soldiers also defended Stalingrad and Moscow, froze in the Kalinin swamps and the Arctic snows, and marched to Berlin.

Twelve inhabitants of Kotlas and the Kotlas District earned the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, seven of them posthumously. City streets and schools bear their During the war, around 40,000 men from Kotlas, the Kotlas District, and other nearby districts were called into the army through the Kotlas military command. More than 12,000 of them perished in battle, and almost 4,000 were missing in action. In memory of the citizens of Kotlas who gave their lives for the Fatherland during the Great Patriotic War, an eternal flame was lit at the monument to our fallen countrymen in the park next to the Palace of Culture of the railroad workers. This flame was lit on May 9, 1975, in honor of the 30th anniversary of the victory, from a spark from the blast furnace of the Limenda shipyard.

The postwar years brought significant new development to Kotlas. Industrial production and transportation operations increased, leading to a significant growth in the number of workers and engineers and of the population of the city as a whole. Builders constructed housing, schools, and facilities for children. The central streets of Kotlas began to fill up with three-story masonry buildings. In the postwar years the collective of the largest industrial enterprise in the city, the boatyard at Limenda, introduced a sectional method of building metal hulled boats and barges. The new advanced technology of construction allowed organization of an assembly line and assured growth in productivity of 30-40% while lowering the cost of production. The railroad workers of Kotlas also had great accomplishments. Advanced methods of running trains were widely adopted. In 1949, the settlement of Vychegodsky grew up next to Kotlas. There the Solvychegodsky Division of the Northern Railroad was established, with a marshaling yard and locomotive and railway car depots. The engineers of the Solvychegodsky Depot mastered the art of pulling trains of double weight with a single locomotive. In 1957, Kotlas got a new building for the railway station. In the postwar years the turnover of freight at the Kotlas River Port grew. The freight yard "New Branch" received completely new equipment and mechanisms. The amount of freight handled at "City Yard" also increased greatly. The timber trans-shipping bases became especially important. They supplied lumber to regions devastated by the war. In 1953, the log rollers of the Boltinskaya base, with the support of the workers of the Kotlas-South railway station[i.e, the main train station in Kotlas], adopted a method of loading timber into the wagons without padding, greatly increasing the load that a four-axle wagon could carry. At the same time the method of loading the timber "with a cap" was developed at the lumbering bases. Given the shortage of railway cars in the country, this method had great significance for the national economy. The Ministry of Transportation decided to make this method the standard for all the railroads of the country. After the war, a unified network of vehicular roads was created, stretching about 20 kilometers, linking almost all the settlements of the city. After the war, the network of health care institutions expanded. In the city there were already 6 hospitals, 5 polyclinics, 1 ambulance service, and 7 medical stations. The rapid growth of the population made it necessary to increase production of consumer goods. Bringing them in from other cities didn't make sense, so local and cooperative industries began to make them. The Municipal Industrial Combine took a leading role, producing stitched goods, furniture, and mirrors. In the 1960's, construction of four- and five-story apartment buildings began in Kotlas. Also, the pedagogical training school, a hotel, the airport, the telephone station, new schools, kindergartens, nurseries, bath houses, and other cultural and social facilities sprang up. In 1953, on the shores of the Vychegda [which flows into the Northern Dvina at Kotlas], in the settlement of Koryazhma, construction of the largest cellulose-paper combine in the Soviet Union and in all of Europe, which had started during the third Five Year Plan, resumed. Thousands of construction workers under the auspices of the Komsomol [the Communist Party organization for young adults] came to build this combine. [Prison labor was also used. See "Kotlas and the Gulag".] The construction work was youthful and bold. In 1961 the combine produced its first cellulose; the second line went into production in 1965; and the third in 1972. The Kotlas Cellulose-Paper Combine includes sulfite-cellulose, sulfate-cellulose, biochemical, fiberboard, and forest-chemical plants, as well as three factories: paper, cardboard and paper bag. The combine produces about 20 different products, and has sold to 2,500 customers in the U.S.S.R. and in 26 foreign countries.

Today, Kotlas is the seat of the Kotlas District of the Archangel Region. The population of the city on January 1, 1997 was 82,300. Kotlas is a city of railway workers, river transport workers, timber processors and machine-tool manufacturers. Oil and gas pipe-lines pass through Kotlas to the center of Russia. Kotlas is the third largest industrial center in the Archangel Region. Among the main industrial enterprises in the city, the following should be mentioned:

Kotlas is the largest railway junction on the Northern railroad, with connections to Vologda, Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Archangel, Kirov, Syktyvkar, and Vorkuta. The city is also a major river port. The waterways connect it with the districts of the Archangel Region, as well as the Vologda Region and the Komi Republic. The Kotlas airport has flights to Moscow, St. Petersburg, Archangel, Murmansk and the other districts of the Archangel Region. Construction began in 1986 of a new hospital complex with a polyclinic serving 1200 patients a day, a hospital with 710 beds, and a birthing center. There are 14 regular public schools, two residential schools, a youths' sport school, and the House of Children's Creativity [similar to a Boys Club/Girls Club]. Professional training is provided by vocational schools for primary school teachers, health care workers, and river transport workers. There are also three vocational-technical schools. The city has a drama theater, two music schools, a local history museum, a system of libraries, a Palace of Culture, two clubs, a center for folk art and recreation, and a private art school. Further Reading: "Kotlas and the Gulag" |